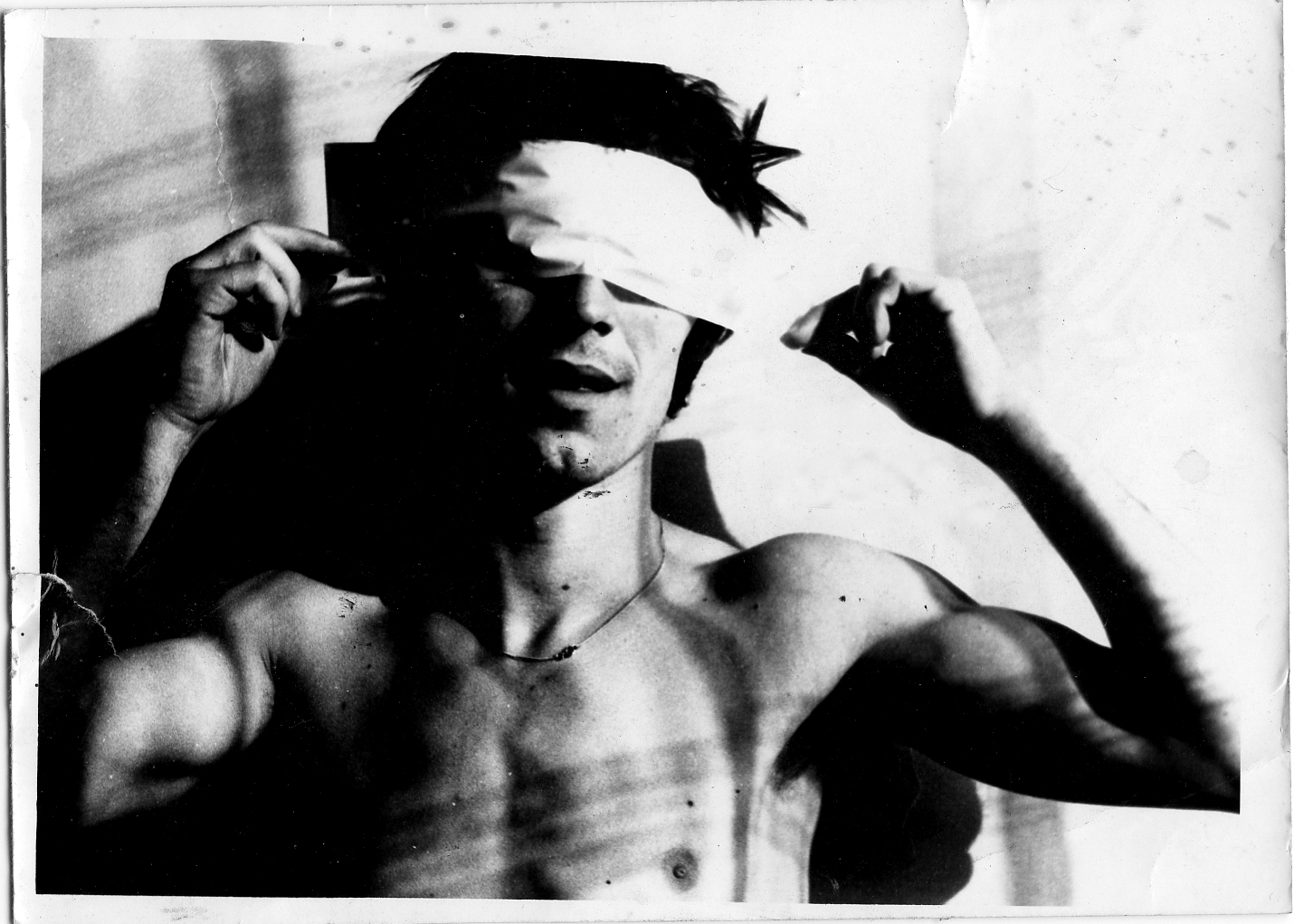

Selfie (1970)

Selfie (1970)

„Gábor Tamási has been involved in photography since 1970. Until 1975 he worked as a photographer for the Museum of Ethnography, and until 1980 he was an external contributor for Mozgó Világ magazine. He worked as a studio director, book publisher, and commercial photographer until 2012. Since 2001, he has been primarily interested in documentary photography; his main themes are urbanization, semiotics, and the impact of civilization on the environment. Since 2003, he has passionately explored the urbanization problems of industrial landscapes, buildings, and factories. In his work, he is equally interested in the fate of industrial facilities and buildings that are disappearing or transforming, and in the situation, life, and everyday reality of the people who work in them.“

On the Left Hand of God – Photographs by Gábor Tamási April 11, 2015 – May 13, 2015, Artézi Gallery, Budapest (Óbuda), Kunigunda Street 18 By Csillag Deák

Ladies and Gentlemen, dear audience,

Gábor Tamási’s career as a photographer began more than forty-five years ago, and thanks to his inquisitive and searching nature, his uncompromising commitment to quality, his strong poetic affinity for photography, and his artistic sensibility, he has had the opportunity to master every aspect of the craft — to experiment with many genres of expression through light, to establish his own studio, and to create and operate creative workshops.

This versatility goes hand in hand with the fact that defining Gábor Tamási’s artistic personality is no simple task. What seems certain is this: starting from applied photography, and equipped with all its technical knowledge, he has moved toward social documentary, figurative imagery, portraiture, and creative photography. This foundation — ranging from still life and commercial photography to reproduction and computer graphic design — has made him a master photographer, and this professionalism has characterized his artistic photography from the very beginning. Like every artist, he has had his early works, but — from the perspective of craftsmanship and technical skill — never weaknesses; his beginnings were free of any amateur elements.

As I see it (others may think differently), until the turn of the millennium, his main focus and attention were largely sociographic: man and society, man and settlement, the destruction of values and the survival of the valueless — and the complex interplay among all these. This was a period of soaring visuality — the rivalry and transformation of analog and digital image-making, their mutual provocation and search for new functions — which gave rise to a multitude of new genres in the visual arts and broadened the field to encompass visual communication itself.

In the first decade of the new millennium, this visuality, this culture of images, began striving for hegemony over textuality — over the Gutenberg Galaxy. We know that new currents always surge forward like great waves, but after their expansion — within new structures — both the new and the enduring old values find their rightful place and proportion.

In the realm of artistic photography, this probably means a weakening of the reproductive and documentary functions and a strengthening of the metaphorical — even magical — function.

For me, Gábor Tamási’s photographs from the past decade and a half already embody this new quality: the extraordinary intensification of metaphorical depth, and the entry of conceptual elements — in both literal and figurative senses — into the image itself.

A beautiful realization of the omnipotence of image and text together is his 2004 album Something Remains (Valami megmarad). Self-contained images and lyrical thoughts appear side by side, emerge, submerge, interweave, and through this intermedium they create an entirely new artistic quality. Both the photographs and the poems are Tamási’s own, showcasing his iconographic and poetic sensitivity alike.

His 2012 album Requiem was created in collaboration with poet István Kis Pál — an experiment in a dual-author montage of icon and text. He achieved this in such a way that the equality of the two worlds is unquestionable: the image does not become an illustration, the text does not provide explanation or didactic support. Words form into icons, and the suggestive power of the images sharpens and crystallizes them.

Their fusion is intensified to the utmost by the lyrical associative power of the images and the highly visual, flickering imagery of the text. One may justly say that with this volume, a new genre was born — although its distinctiveness is so pronounced that the audience — viewer, reader, and critic alike — still needs time to grasp its full significance. And now, a few reflections on the current exhibition, whose title takes its metaphor from Ady. With it, the artist places both himself and his works — together with us — on the left hand of God.

We know well that the left side is not the side of salvation or redemption, but of sinners, the errant, those who pile error upon error, those unable to look toward the Redeemer — in short, our side: humanity’s. This placement on the left is our inherited point of view, from which we can regard our own way of seeing the world, our mythological and transcendental connections, the weakness of our virtues and the strength of our frailties. We know how much we sin against our future; we experience daily the fragility of our civilized shell, yet we still fail to restrain our self-destructive and nature-destructive tendencies.

Among the photographs, Message from the Past (Üzenet a múltból), for me, most clearly expresses the thousandfold web of dependencies and connections, and the uncertainty and contingency of cultural codes. Like archaeological layers, the positive and negative imprints of standard prohibition signs have been superimposed upon one another. Black, white, and red hieroglyphs send messages — but the overlapping layers increasingly obscure the possibility of decoding them. (It brings to my mind Péter Esterházy’s object piece, in which he rewrote, in continuous handwriting, hundreds of times over each other, Géza Ottlik’s novel School at the Frontier on a 57×77 cm sheet of drawing paper, as a birthday gift for Ottlik’s 70th.)

Then, looking further at this photograph, the first and last lines merge and align: the first reads “Attention!”, the last “Effectively forbidden!” Yes, this is indeed a message from the past — and with enough life experience, the intervening lines can be filled in many ways…

Another photo, titled Nothing Moves (Semmi sem mozdul), presents us with a living contraption — a welded steel frame painted green, with a living surface attached to it — what soldiers used to call a stoki (stool). The picture might be called documentary or sociophotographic, yet it is not, for the wind of change has shifted this object, revealing the chemical rust mark that has etched itself into the concrete through a temporary timelessness. Babits wrote: “Objects too have their tears” (Sunt lacrimae rerum). The object, displaced from its original value and context, therefore no longer merely documents — it no longer declares, but exclaims!

His Still Life (Csendélet) was taken at the site of the Józsefváros market. Amid the ruins of demolished stalls — now reduced to dust and splinters — a mannequin head gazes pensively into itself. This is such a powerful, even provocative metaphor that I accused the photographer of staging it, of placing the mannequin head atop the heap himself. I could not believe that reality could randomly create such a potent symbolic association. Yet it turned out I was wrong. This type of image is immutable, unalterable.

Picasso once said: “I do not seek — I find.” Likewise, Tamási’s moments are not sought but found. What for us might be mere spectacle — if we even notice it — for him is already subject matter that must be seen, not merely looked at, and shown photographically through the tools of photography: form, color, proportion, depth, resolution, nuance. We, as laypeople, may perhaps notice a motif that suggests a strong symbolic system — “there’s something in it,” we might say — but we do not know what to do with it.

The artist, however, possesses an incredibly sharp and swift eye, a nervous system tuned for iconic operations, the ability to react within fractions of a second, and the mental capacity to execute the dozens of steps in forming and shaping an image. And also — innate gifts: patience, humility, boundless empathy, and a profound commitment to humanity.

In his Old Prefabricated House Factory (Régi házgyár) series, however, it is true that elements of reality, distant from one another, could only be brought together in a single image through deliberate composition — for here we are dealing with a visual metaphor and symbol that chance alone cannot create, but only creative design. The monstrous concrete columns, revealing an inhuman world, again recall Babits for me: “Torn wires hang like last year’s weeds, / and the scrap of iron covers distant fields” (God and the Devil). The young dancers, for me, represent the utmost counterpoint — appearing in the very last moments of decay, evoking “the men who have become their own murderers” (ibid.). The artist achieves all this through the cathartic, awakening power of art — and, with Ady’s moral sensibility, still offers a faint ray of hope, using art’s magical function to embody and dispel fear. “I thought: my dear little companion, / let us try yet to remain / in this murderous, wild collapse.” (But What If Still?)

The photograph numbered 18 in the catalogue, taken at the Józsefváros railway station, was inspired by the penultimate moment. Tamási told me that its textual background is Bob Dylan’s song Knocking on Heaven’s Door*.

The association is remote: in the lyrics, these are the final moments of a mortally wounded deputy sheriff, when “a long, cold black cloud is comin’ down,” and “I feel I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door.” The door is still half-shut, half-open. And behind it — what awaits us? Final darkness or illumination?

In conclusion: Gábor Tamási is a man of signs, a master of signs. For him, the image is a word, the word an image; he seeks, reveals, and leaves signs — hopefully within us as well. He urges us to work — to interpret, to feel, and to understand these signs. To sense the anxiety for values, for humankind, for freedom. To recognize what we have done wrong, what we have almost irreversibly spoiled. Our footprint has grown far too large; biological life itself is in danger, our air is running out, our sins are many, and our humanity is at risk. Let us, therefore, heed the warning voice of art!

Sándor Csokonai-Illés Delivered at the opening of Gábor Tamási’s photography exhibition in Szekszárd, April 12, 2016.